|

WINGS TAKE OFF

Paul wanted to be back in a group. He wanted to feel the internal dynamics of a band at work. He needed to get the feedback of working with other musicians; to build up a song, layer upon layer, as each member contributed something new. But he didn't want to recreate the Beatles. He didn't even want any comparison with them. This time it had to be his own group, one in which he would have the last say.

When he asked Denny Seiwell to join in early '71, he probably only had the vaguest idea about the rest of the band members. Already his choice of musicians was unusual - a complete amateur in Linda and a virtual unknown in Seiwell.

Denny Seiwell might be a name in New York session circles but he meant little to the British rock fraternity. His background, however, was impeccable. He was a born drummer - "I've never practiced the drums," he once said, "I've just played them" - following his father who had earned his living at it until the responsibilities of bringing up a family forced him out.

He started in earnest at the age of seven, playing snare in a boy's orchestra in his home town of Leighton, Pennsylvania and continuing through high school. Rather than waiting to be drafted, Denny signed on for a four year stint in the army as a bandsman. He did a lot of travelling during his service and he was particularly impressed by the Latin American rhythms he learned in Brazil - rhythms that were later to sweep the world as Bossa Nova.

In the early'60s he was out of the army and in Chicago, playing jazz in cellar dives and starting on a long haul towards recognition. He gravitated towards New York and was soon playing the best jazz clubs, gaining the attention of other musicians. His versatility won him a place on the roster of highly-paid sessionmen. This work required him to be able to play in any style and to get it right first time. The pace was hectic: "You get three tunes done in three hours - I've made an album in a day!" But although it was financially rewarding, he found it artistically stifling: "There would be about one session out of every five that was worth playing."

By the time Paul was searching New York for a good session drummer, Denny Seiwell had just about had enough. "I was dying to get out of the studios," he later said. "Everybody was saying I was crazy… not taking morning jingles every day. If you don't play live dates the studios can drive you nuts."

After working for McCartney on Ram he realized he could fit in with his methods. "It's a nice way to work. When we made Ram Paul would run through a song a couple of times, we'd check out a couple of parts and do takes in a few minutes." They worked fast and understood each other. When the possibility of a group was mooted, Seiwell was ready and willing.

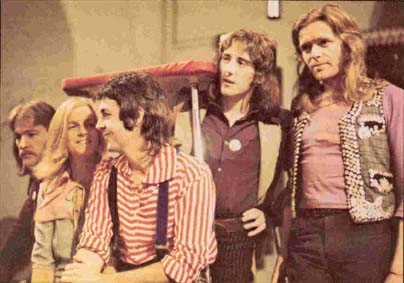

And then there were three - bass player, keyboards and drums - although the drummer could also play brass and the bassist could play just about anything you care to name. Now McCartney needed at feast one more musician - preferably a good voice for harmony work and an accomplished guitarist. His choice was another Denny - Denny Laine.

Laine and McCartney had been a mutual admiration society for years and often spoke about each other in private conversations and in interviews. Denny Laine was born in Birmingham with the name Brian Hines. He was part of the city's active musical scene and played in a variety of groups with the Brum musicians who would eventually emerge into the international limelight as members of the Spencer Davis Group, Traffic, the Move, Wizzard, Electric Light Orchestra and so on. The Birmingham band that brought him success was the Moody Blues.

Laine (with his raw-edged voice) and the Moodies made one of the classic British hits of the '60s beat boom - Go Now! Due to their immaculate image, their tag "The Magnificent Moodies" and their musicianship, they enjoyed a cult reputation in both Britain and America (where Linda Eastman was an early, enthusiastic fan with a burning but unrealized desire to shoot a session with them). Sadly, their chart success did not match their reputation and while they made a good steady living playing Europe on the strength of the one massive hit, they didn't seem to be getting anywhere. Laine, who's always been footloose, left.

He had some unusual and rather advanced ideas about the way that rock in the '60s might develop and he set up as a solo singer/songwriter. Sadly, from leaving the Moody Blues to joining Wings, his several interesting projects never entirely succeeded, either because they were about two years ahead of their time or due to lack of finance.

In the mid-'60s he was signed to Decca's new 'progressive' label Deram (which also recruited the talents of Cat Stevens, the Move and, ironically, the Moody Blues in time for their revival) and caused a great deal of interest in '67 with his brilliant song Say You Don't Mind. Both the song and the performance were flawless but somehow failed to catch the public ear. Say You Don't Mind didn't achieve the recognition it deserved until five years later when ex-Zombie Colin Blunstone took it to number 15 in the UK charts in 1972. The song was as good as ever but Blunstone's performance lacked Laine's sensitivity. (Decca unsuccessfully re-released the single In January, '72, shortly after Wings' first album was released.)

Denny appeared at one of Brian Epstein's celebrated Sunday night concerts at the Saville Theatre, London that same year with an ambitious project called the Electric String Band. This was a group of classically-trained violinists and cellists whose instruments had been amplified to give a full, rich sound that buttressed Laine's excellent songs. Their debut was complicated by technical problems but showed a great deal of promise and Denny with his superb voice, evident songwriting talents and attractive personality seemed set for stardom. But in this, as in so many other ventures, he was frustrated. "The String Band could have worked," he said years later. "It was way before its time .. .but I just didn't have enough money to play around with."

The next few years saw him involved in several schemes which were interspersed with trips abroad, including a year in Spain, living like a gypsy and learning to play authentic flamenco. He became part of Ginger Baker's ambitious and unwieldy Airforce, collaborated with ex-Move Trevor Burton on the Uglies and poured a lot of time and energy into another group, Balls, that had a shifting personnel including Burton, Steve Gibbons and Alan White before fizzling out after a few gigs and one record.

He returned to solo work again and was working on an album of his own songs when McCartney called and suggested he might be interested in working with him. No second bidding was necessary, he dropped his own material and hastened up to Scotland to meet Denny Seiwell and talk over plans with Paul. Soon they were playing together and laying down the tracks that made up a new album - Wildlife - by a new group - Wings.

Wildlife was recorded during August 1971 by a group still without a name. Early in September Linda went into Kings College Hospital for the birth of her third, Paul's second, child. As had happened when Mary was born, Paul moved into the hospital as well, intending to be present at the birth. Unfortunately, there were complications and the baby had to be delivered by Caesarian section. Paul was barred from the operating theater and, as he told the London Sunday Times, "I sat next door in my green apron praying like mad… The name Wings just came into my head." Linda maintains he was thinking about "Wings of an angel."

Thus Stella McCartney and Wings were born on the same day - September 3,1971.

Wings released Wildlife in December to adverse criticism. Someone had coined the phrase "Suburban rock & roll" to describe Ram and the sneers continued. It wasn't a remarkable album and was less popular with the public than its predecessor, reaching numbers 8 and 10 in the UK and US charts respectively. It seems that McCartney recognized that it was not his finest work because no singles were taken from it. He later admitted that "it wasn't that brilliant as a recording." It had been put down in about a fortnight with a group whose members barely knew each other. One thing that Paul had learned from the Wildlife sessions was the need for another musician - a guitaris - particularly as he was thinking of taking the big step of going out on the road and playing gigs. He hadn't played before an audience since the Beatles' last concert in San Francisco in 1966, even though he had tried to persuade the others to tour in the later days. Now he was attracted by the possibility of getting out among the people.

Any guitarist brought into the fledgling Wings would have to be prepared to go on the road. Denny Laine realized this when he joined. "I was ready to go on the road when Paul called me," he later remembered, "and I knew Henry McCullough was too - so I told Paul about him, and that's the way it came about."

Henry McCullough was, and remains, one of rock's more enigmatic figures. His career has been chequered, as he has drifted from band to band, seldom staying long but usually increasing his reputation as a fine guitarist. Born in Ireland, he started his musical life with touring showbands. These are uniquely Irish combos that criss-cross the country, gigging in the rundown dancehalls of small towns and expected to play something to entertain everyone. One number will be rock to satisfy the teens, the next might be a comedy/novelty item for their parents and they may top this off with a traditional air to please the elderly members of the audience.

McCullough stood apart in this milieu, always the long-haired rocker amid the glistening smiles, tacky stage suits and slick routines of his contemporaries. His inclination was always towards rock and eventually he teamed up with some like-minded friends to form the cutely-named Eire Apparent. They, like so many hopefuls before them, trekked across the Irish Sea to find recognition in Britain and, by an extraordinary stroke of good fortune, were spotted by Chas Chandler.

He thrust them into the spotlight by putting them downhill to his major artist - Jimi Hendrix. It was a mixed blessing because it got them - and McCullough in particular - noticed but they were frankly over-shadowed, outplayed and outclassed by the Experience. Things started winding down and, somewhat disillusioned, Henry drifted back to Ireland.

He found further partial success with Sweeney's Men, playing an Irish folk/rock fusion that resulted in local hits but little financial reward. He crossed the sea again and had a further piece of luck in meeting Joe Cocker and joining his Grease Band. Cocker was just emerging internationally and starting to enjoy the rather brief but very considerable success that followed With A Little Help From My Friends and Delta Lady. Henry accompanied him on the storming tours of the States and started building up g name as a guitar virtuoso.

Just as things were looking good, Cocker - worn down by the strains and enticed by the Mad Dogs And Englishman roadshow - split. The Grease Band struggled on for a while before breaking up. "It was so loose," Henry told the music press after joining Wings. "We could never get anything together; we'd play the same songs every night and they'd always be different."

A man with so much varied experience behind him could only be enticed by an offer to join what was potentially a smash hit group. After all his ups and downs, his near-misses at stardom. Henry McCullough was faced with his best chance yet of making a lasting impression on the public mind.

The new year that saw Henry McCullough's entry into Wings brought with it controversy. In February, 1972 the group released a single called, unequivocally, Give Ireland Back To The Irish. It was McCartney's genuine and heartfelt reaction to the events of Sunday, January 30,1972 - known in Northern Ireland as 'Bloody Sunday'. On that day 13 Catholics were shot dead by British paratroopers after a civil rights demonstration in Londonderry. The troops claimed that they were replying to sniper fire.

There was a feeling of shock and outrage inside Ireland which was shared by many people in mainland Britain, including Paul. He told a reporter that he wrote the song because "the day after the paratroopers went in, everyone thought 'Hey! That's just a bit too much.'"

He admitted that he found himself in a quandary. "If you're in the position of being a songwriter who can make a comment, you're faced with the decision of either saying nothing about it which is fair enough and keeps you cool, or taking the risk of saying something about it and being a little uncool, because it's uncool to say anything political, let's face it."

In the event, he let his emotions rule. Give Ireland Back To The Irish was written in the heat of the moment. It was rehearsed and recorded within one day and on sale inside a month. At which point the ВВС banned it from the air for its overtly political content. The fact that it wasn't getting airplay did not stop it reaching number 16 in Britain. (It got to 21 in the States. A creditable effort in a market for which it presumably had little relevance.) Nor did it make McCartney regret his stance, even though many were surprised at politics springing from his pen; that was surely something he'd always left to John?

As he told Sounds later that year: "Our government happened to be shooting Irish people, and I thought that was real bad news and I felt I had to say something about it. I'm glad I did because looking back on it, I could have just sat through it and not have said anything. But it was just that it got so near home on that particular day I felt I had to say something ...

"I like the Irish. I dig 'em all. North, South or whatever... I've never met an Irishman I don't like ... The British and the Irish, they're like the same people, particularly for me coming from Liverpool - I'm sure I'm Irish way back somewhere. So it just got to be very personal, the whole thing."

There's no doubt that McCartney's view was not one held by all Britons at that time. And there must have been many - British, Irish or even Ulstermen of both persuasions - who found his views naive. But none could have doubted his sincerity nor the undisguised horror that prompted his song.

Wings didn't have much time to worry about the ban for they were preoccupied with organizing their first public outing together. As with so many other McCartney projects, this was to be unorthodox. He was acutely aware that the group were still getting to know each other and not nearly ready to undertake a full-blown tour that might be expected of a band with an ex-Beatle heading it.

His major problem was that the public would expect so much of him. This was coupled with the fact that he had one completely inexperienced performer in his ranks. Indeed, Linda found it hard to share his enthusiasm for going out and putting on a show. She told the Sunday Times: "He went on and on about it, saying he was dying to get back to performing, but wanted me to join in. 'Can you imagine standing on the stage, the curtain going up, the audience all waiting ...' He made it sound so glamorous that I agreed to have a go."

A further complication was the attitude of the press, expecially the rock media. They'd already been sniping at him for Ram and Wildlife, there'd been sneers about Linda's role and there would be the unfair but inevitable comparisons with the Beatles' concerts. What he needed was a way of gaining the maximum experience with the minimum amount of press exposure. The best solution seemed to be to take to the road unannounced and turn up to play at previously unbooked venues.

Paul loaded the band, along with assorted wives, children and pets on to a caravan, piled the equipment and a couple of roadies into a van, took to the motorways and headed for whatever university towns took their fancy. Once there they would send in an aide to ask if they could put on a show for the students the next day and, once having obtained permission (who was going to refuse an offer like that?), put the word around the campus. They could set up the gear overnight, go on, do their set, reload the vans and set off for the next town up the road.

The first Wings gig ever - and Paul's first appearance before an audience in nearly six years - was at Nottingham University. The venue was chosen on the simple basis that it was the first they chanced upon. Road manager Trevor Jones once described the organization (if something as casual can be so termed) that went into it: "We went into Nottingham University Students' Union at about five o'clock and fixed it up for lunchtime the next day. Nottingham was the best because they were so enthusiastic. No hassles. No-one quite expected it or believed it. We went down there at half-past eight the next morning with the gear. We threw a few posters up and put the word out on the tannoy."

At lunchtime on February 9, 700 students filed in to watch a new band. "It was 50p at the door," Paul later recounted with obvious pleasure, "and a guy sat at the table taking the money. The kids danced and we all had a good time. The Students' Union took their split and gave us the rest. I 'd never seen money for at least ten years. The Beatles never handled money... We walked around Nottingham with £30 in coppers in our pockets." Wings were in business.

Delighted with their first excursion into public playing, the band hit the road again and progressed along the motorway until they came to Leeds in Yorkshire. Here the same casual introductions took place again, and here they hit their first snag. As they were starting their set, Paul counted them into the opening number, Wildlife, but nothing happened. Linda was paralyzed by fear and quite unable to put her hands on the keyboard. She had advanced stage-fright. Hardly to be wondered at, considering she had been playing keyboards for less than a year, learnt from scratch and was only appearing before an audience for the second time in her life! Paul rushed to her assistance but found that he too had forgotten the opening chords! The students cheered good-naturedly.

As their journey haphazardly continued, a number of university towns reluctantly had to decline their offer due to exams being held or lack of a hall large enough to accommodate the crowds that would inevitably gather. However, by the time the roadshow reached Lancaster University, the press had caught up with the wandering band and was eager to know exactly what the McCartneys thought they were playing at. Relaxed after the tensions of her ordeal in front of an audience, Linda was feeling more confident about meeting reporters and stepped into the front line.

She told Melody Maker how satisfied she was with the progress so far. "We've only been playing together for five days and already I have confidence in the band. So far audience response has been good. Surprisingly perhaps I am enjoying these one-night appearances - it's like a touring holiday!"

And what was the reason for the unscheduled gigs? "Well, we just don't like to be tied down. If we wake up one morning and decide that we don't want to go to, say, Hull, we don't have to! With an organized tour your freedom is limited. This is the only way to do it!

"Eric Clapton once said that he would like to play from the back of a caravan, but he never got around to doing it. Well, we have! We've no managers or agents - just we five and the roadies. We're just a gang of musicians touring around."

The adventure proved that Wings were a band capable of performing in public despite its youth and the inexperience of one of its members. Content that they had scrambled through the first phase, McCartney now turned his thoughts towards a more ambitious tour later in the year. In the meantime, the group released the second of three controversial singles that year.

Nobody tried to ban Mary Had A Little Lamb but there were plenty who thought it should never have been released. It could not have been in greater contrast to Give Ireland Back To The Irish. The latter was angry and political while Mary was a whimsical reworking of an old nursery rhyme. It was as if every accusation hurled against Paul of creating "suburban rock," of being little better than Humperdinck, was coming true.

The fiercely 'anti' reaction to it by the rock press may have taken McCartney by surprise. It's possible that he had not realized quite how incongruous the two last singles sounded. Critics could not understand how the same writer with the same group could come up with two such dissimilar discs. When tackled with this point by Sounds, Paul seemed to scratch his head before answering. He didn't have a pat answer to it. His best response was: "I'm crazy. I've always been crazy from the minute I was born... Geminis are supposed to be very changeable, and I don't know if that's true or not but I'm a Gemini and I know one minute I might be doing Ireland and the next I'll be doing Mary Had A Little Lamb. I can see how that would look from the sidelines, but the thing is we're not either of those records, but we are both of them."

If there is one thing that links the two, it is depth of feeling. Both sprang from inside Paul; Ireland in anger, Mary in love. "Mary Had A Little Lamb was just a kid's song," he told the same interviewer. "It was written for one of our kids, whose name is Mary, and I just realized if I sang that, she'd understand. That's it with us, that's what you might expect from us - just anything."

In retrospect, Paul was to admit that Mary "wasn't a great record." However, he pointed out that it went down well at live shows and that there were quite a few people who did enjoy it. "The quote that sums up that song for me is I read Pete Townshend saying that his daughter had to have a copy ... I like to keep in with the five year olds!"

During 1972 Paul McCartney declared: "We're just now into a new band. We can see all the new possibilities of working different ways. It's all open . .. it's like a blank canvas." He was keen to start filling in the brush strokes and now looked towards Europe for his next excursion. He was determinedly trying to live down comparisons with the Beatles; he wanted the band to be accepted as Wings and not as ex-Beatle Paul and his little group. He felt that the Continent would perhaps give them a fairer hearing on their own merits and that by playing reasonably large venues there it would serve as a dress rehearsal for full tours in Britain and, ultimately, America.

Although a bigger, more organized tour than the previous run round the campuses, the 1972 tour of Europe still retained a family holiday feel. This time the group travelled in a gaily-painted, open-topped, London double-decker bus, setting off in July to undertake a seven week trip through France, Germany, Switzerland, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Holland and Belgium.

This time, they were under the close scrutiny of the British press whose reaction ranged from antipathy to grudging praise. The band's first gig was a modest affair in an open air setting at Chateau Vallon near Toulon in the South of France. Press observers noted that Paul was evidently enjoying himself and that he "commands a respect... few others could hope to receive." The 2000 paying customers were described as "enthusiastic but undiscriminating" and while the band generally gained plaudits, one member was singled out for brickbats. "Linda vamps at the keyboard . .. and chirps in with vocals here and there. Unfortunately, her voice tacks both depth and power, a fact which McCartney must know all too well."

The press continued to nip at McCartney's heels throughout the tour, the national newspapers blowing trivial incidents up out of all proportion. One reported: "At virtually every hotel there have been tantrums because the McCartneys will not accept the conventional Scandinavian single beds. The attitude seems to be: ' I want it, therefore it must happen.' " This piece also contained a quote from an unnamed "friend" who said of McCartney: "He lives in a fantasy world. He has been cocooned so long by his money, fame and his own seclusion that he is out of touch with reality."

Other papers - mostly the rock press which is not so bent on sensationalism - noted that Paul was not so out of touch that he couldn't please his audiences. They seemed to enjoy the band and greet it enthusiastically even though McCartney refused to include any song associated with The Beatles in the set. The people who paid money for their seats may have concurred with a critic from one of Britain's national newspapers (even if his tone was offensively blunt) who remarked: "It is no secret that Linda... has a voice that can be upsettingly flat and is in the kindergarten when it comes to playing the organ." But they patently did not agree when he went on to say: "Wings, musically, never takes off. At their best they are uninspired. At their worst mediocre. McCartney, wandering minstrel, hasn't made it."

The newspapers had plenty of front page material to splash towards the end of the trip, when the group reached Gothenburg in Sweden. Wings were playing the Scandinavian HalI and at the end of an enthusiastically received set the p.a. system was abruptly cut off by the police who were waiting to question Paul, Linda and Denny Seiwell about seven ounces of marijuana that customs officials had intercepted. It had been sent from London and, they alleged, was addressed to Paul.

Amid scenes of confusion in the dressing-room - caught by the tour photographer Joe Stevens and splashed across newspapers the next day - the three together with Paul's secretary Rebecca Hinds were taken away for questioning at police headquarters. Later a senior officer in the Gothenburg police addressed waiting pressmen: "We told them we had found the cannabis in a letter and at first they said they knew nothing about it. But after we had questioned them for about three hours they confessed and told the truth. McCartney, his wife and Seiwell told us they smoked hash every day. They said they were almost addicted to it. They said they had made arrangements to have drugs posted to them each day they played in different countries so they wouldn't have to take any drugs through the customs themselves."

This version differed in several respects to one offered by the tour organizer, John Morris. He told reporters: "Paul, Linda and Dennis did admit to the Swedish police that they used hash. At first they denied it but the police gave them a rough time and started threatening all sorts of things. The police said they would bar the group from leaving the country unless they confessed.

"The drugs were found in a parcel addressed to Paul by customs men. Lots of people send drugs to the band. They think they are doing them some kind of favor. Instead it causes all this sort of trouble. I'm not prepared to say whether Paul has been posted hash before during this tour or whether he smokes the stuff. It was simply a case of pleading guilty, paying the fine and getting out of the city. As far as we are concerned the whole business is finished."

The public prosecutor of Gothenburg, Mr Lennart Angelin, said that the accused had been released after paying a preliminary fine of about ₤1000. He explained: "They were not arrested since it was obvious that they were going to use the cannabis themselves and not pass it on... They are free to carry on their Scandinavian tour or leave the country."

Paul McCartney was later reported as saying: "The Swedish police behaved correctly. Unfortunately, they take hashish and marijuana far too seriously." An unidentified member of the group was supposed to have said, with surely more bravado than serious intent: "The police action against us was an excellent advertisement. Our name flies now all over the world."

The matter was over and the tour continued but it certainly was not the end of this year of controversy. After the group's return to Britain, a search was instituted by police on the McCartneys' Scottish farm and, as a result, Paul was ordered in December to appear before a court in March the next year to answer three charges regarding cannabis possession and the cultivation of cannabis plants.

Before the case was heard, Wings issued their third single of 1972 - Hi, Hi, Hi. And, like the other two, it ran into trouble. It was their second song to be banned in that year. A spokesman for the BBC confirmed that Hi, Hi, Hi would be played on neither Radio 1 (the pop station) nor Radio 2 (which specializes in easy listening) because of Its content. "The ban has nothing to do with drugs," he said. "We thought the record unfit for broadcasting because of the lyric. Part of it goes: 'I want you to lie on the bed and get you ready for my body gun and do it, do it, do it to you.' Another part goes:

'Like a rabbit I'm going to grab it and do it till the night is done.'"

The irony of this banning lies in the fact that Paul never wrote a line saying "get ready for my body gun." 'The lyric as he wrote it was "get ready for my polygon." He admitted that it was intended to be suggestive but in an abstract way. He wanted the suggestiveness to be oblique, whereas "body gun" is quite explicit. The confusion occurred because the publishers, Northern Songs, had misunderstood or misheard the lyric and transcribed it wrongly. At first the BBC were worried that Hi, Hi, Hi might contain drug references and wanted to see the printed lyrics. Instead of drugs they found sex! Or thought they did.

In the event, it hardly mattered because the disc's other side - C Moon - was so strong it hit the Top 10 In both America and Britain. Curiously, this number did contain a coded message, but nothing to alarm the guardians of Britain's morals at the BBC. Paul explained it to Sounds: "Remember Sam the Sham and Wooly Bully? Well, there's a line in that that says 'Let's not be L7' - and at the time everyone was saying 'what's L7 mean? ' Well, L7, it was explained at the time, means a square - put Land 7 together and you get a square... So I thought of the idea of putting a C and a crescent moon together to get the opposite of a square. So C Moon means cool."

If 1972 had been a traumatic year for Paul McCartney and Wings, the prospects for a peaceful life in early '73 weren't much better. The first major hurdle to be negotiated was Paul's summons to court in Campbeltown to face charges of growing cannabis. The hearing was set for March 8 and the McCartneys flew up to Scotland from London in a hired executive jet to attend.

The court heard that during the previous September a crime prevention officer had gone to the McCartney estate - two farms called High Park and Low Ranachan - to check that it was secure while unoccupied and noticed five plants growing in the greenhouse along with tomatoes. He had become suspicious and, on returning to the police station, had consulted a reference book that had identified them as cannabis. As a result, three charges were brought against McCartney - one of knowingly cultivating cannabis plants to which he pleaded guilty and two others of possessing and having control of cannabis to which he pleaded not guilty and which were subsequently withdrawn.

As in the Gothenburg case, McCartney's lawyer claimed that Paul had received some seeds through the post from a fan. He said that his client had a genuine interest in horticulture. He warned that a conviction on this charge could have serious effects on McCartney's career. "We understand the immigration authorities in the US will refuse admission to a person who has a conviction even though of a relatively technical character," he told the court.

This was no empty warning because in that very month came news from the States that the Immigration Department had ordered John Lennon to be deported from the country as a result of his conviction for possession of cannabis resin in 1968. This presaged John's long, wearisome but ultimately successful fight to be allowed to stay in America. The prophecy came true because Paul could not enter the US for some time and the Japanese authorities refused to let the group appear because of the conviction.

Having pleaded guilty, a conviction was inevitable. When it came to sentencing, the Sheriff - Scotland's equivalent to a County Court Judge - said: "I take into account the fact that these seeds were given to you in a gift but I have to take into account that you are a public figure of considerable interest, particularly to young people, and I must deal with you accordingly. The fine will be £100."

The McCartneys were obviously relieved by the leniency of the sentence and later admitted to pressmen that they thought it could have been worse. Paul jokingly commented: "I was planning on writing a few songs in jail." He then expounded his views on cannabis. "You have to be careful," he said. "I look on it like Prohibition in the old days. It comes up like Prohibition but you have to recognize the law. I think the law should be changed - make it like the law of homosexuality with consenting adults in private. I don't think cannabis is as dangerous as drink." He added: "I'm dead against hard drugs."

March was an eventful month in their lives. On the 18th, Wings gave another of their surprise concerts. This one was at London's fashionable hamburger Joint, the Hard Rock Cafe in Park Lane where they played an hour's set to 200 delighted guests who had gathered for a charity concert. It was held, aptly, to raise funds for Release, an organization which helps drug users and young people in trouble.

A few days later, the group released My Love. It was a live recording of the song (dedicated to Linda) that had been laid down on the European tour the previous year. It was more obviously a McCartney product than the three unusual offerings of '72 and quickly became his second (Wings first) number 1 in the States although it only reached number 9 in Britain.

The fact that Wings were more popular in America than Britain (although they hadn't yet played there) was recognized in April when a TV special - James Paul McCartney - was screened in the States almost a month before it was seen in the UK. This was a showcase for McCartney and Wings, made at the behest of Lord Grade for his ATV company (which also owned the Beatles publishing company Northern Songs and was associated with McCartney Music Ltd).

The show's contents seemed to reflect the many sides of McCartney's personality and his diverse, sometimes rather confusing, attitude towards the sort of performer he wanted to be. Here a good hard sweaty rocking version of Long Tall Sally contrasted with a camp Busby Berkeley-style production number complete with Paul hoofing alongside a bevy of leggy girls; shots of idyllic Scottish scenes competed with the 'working class hero' enjoying a singsong in a Liverpool pub; a solo acoustic rendition of Beatiesque Yesterday was offset by Winging Maybe I'm Amazed; the rock superstar one minute became showbiz entertainer the next.

The patchwork nature of the film was bound to elicit a variety of opinions. Perhaps predictably, the rock press was largely dismissive of the "cosy, familiar outlook." Britain's Melody Maker viewed it rather sourly and opined that McCartney "always had an eye and ear for full-blown romanticism, and nothing wrong with that but here . . . he too often lets it get out of hand and it becomes overblown and silly." One segment was singled out as being "particularly sick-making" in which Linda is photographing Paul while he sings love songs. "The effect is... marred a little by Linda joining in with a decidedly flat voice. On the face of it, she does seem to be forever frustrating the best-laid plans of mice and men."

An American critic thought the show "uneven, but it celebrated Paul's various talents. In a visual and musical context the show was an adequate piece of programming and quite an ambitious project." Another rock paper summed it up as "basically light entertainment and no more... a showcase for Paul's amazing ability to be all things to all men, women and little lambs."

Later McCartney was to admit that it was patchy but he strongly denied that he was deserting rock for wider fields. When asked a bout the Hollywood musical routine (which bore clear resemblances to the Your Mother Should Know sequence in the altogether less successful McCartney excursion into TV, Magical Mystery Tour) he said: "I suppose you could say it's fulfilling an old ambition. Right at the start I fancied myself in musical comedy. But that was before the Beatles. But don't get me wrong. I'm no Astaire or Gene Kelly and this doesn't mean the start of something big. I don't want to be an all-rounder. I'm sticking to what I am."

The inclusion in James Paul McCartney of some songs from his Beatles days - Yesterday and Michelle, for example - marked a new stage in Paul's development. Until quite recently he had brooked no mention of, or comparison with, the Beatles. Joe Stevens, tour photographer on the European sortie the previous year, remembered being told sternly not to mention the Beatles. "I think he'd been almost brain damaged for a while from having been Paul of the Beatles," he told one publication. And Paul himself told the Sunday Times that he "shied away" from Beatles songs at first. "They were too big for us. I knew the audience would be thinking: 'Oh, not as good as the Beatles,'" By now he was feeling a lot more confident about himself and the band.

In between the American and British screening of James Paul McCartney, Wings released their Red Rose Speedway album which followed the pattern of several of the recent records by going to number 1 in America but sticking at 5 in Britain. It is not one of McCartney's better albums, Joe Stevens declared: "I thought Red Rose was a disaster and so did everyone connected with it except Paul."

That's not strictly fair. While Paul is committed 100 per cent to a record when he's making it - as, indeed, he has to be - it does not mean that time won't give him a sense of perspective about his work and allow him to see his mistakes. In a newspaper interview in 1977 he said: "Every time I make a record it takes me about three months before I can listen to it... After I heard Wildlife... I thought: 'Hell. We really have blown it here.' And the next one after that, Red Rose Speedway, I couldn't stand."

Linda, being slightly outside Paul's intense involvement in every aspect of making their albums, pinpointed the reasons for the record's comparative artistic failure. "Red Rose Speedway was such a non-confident record," she said. "There were some beautiful songs... there was My Love but something was missing. We needed a heavier sound. Originally the album was going to be a double as we had about 30 finished songs... It was a terribly unsure period."

Speedway's release was part of the run-up to Wing's most crucial test yet - the first full-scale tour of Britain. This was to be the crunch. In the full glare of publicity and with every critic in sight waiting, pen poised, Wings were going to see whether they could make it on the major concert circuit, in front of home crowds who would be as difficult to please as the press. More in some ways because the audiences had the last sanctions - they could sit on their hands, or, worse still, vote with their feet.

It was to be a 17-day, 12-city crisscrossing of the kingdom. Paul realized how vital it was to succeed. In a pre-tour statement he said: "Publicity alone can never do it. The nitty-gritty is the performer clicking. That only happens when the performer has direct contact with his audience."

Wings' flight was to start at the Bristol Hippodrome on May 11 and take in as many major cities as possible. The press were to be formally invited to throw their roses or rotten vegetables (metaphorically) the next night at Oxford. This gave the group the opportunity of a full-scale try-out before being subjected to the public pillories - an understandable precaution when one considers they were playing Britain's bigger venues barely a year after they'd performed their first ever gig together.

Paul was later to assert he was terribly nervous before the tour, but judging by the reactions of the critics after the Oxford show, this was not evident to even the keenest observer. The notices were warm without being adulatory. Best of all, they were generally fair. "If the second night is anything to go by, Paul McCartney's Wings have got off to a tremendous start," said one. "The group gave an extremely tight performance and were able to dramatically raise the pulse-rate of an already enthusiastic audience."

Others commented that the audience were, in fact, rather reserved at first but "that made the band try that much harder." In the end, all agreed, they were won over and responded with genuine abandon and enthusiasm. McCartney had to earn his cheers and screams but that made them all the more worthwhile. This initial hesitancy on the audience's part, a reserve until the band had proved its worth, was a feature of most of the gigs on the tour.

It was difficult to assess how many ticket holders were going in order to see their favorite ex-Beatle and how many were already Wings fans. Linda realized the possibility that many wanted to see Paul but added: "I hope they go away digging it, Paul really digs being in a band. He really loves performing, he loves it to be good and loves things to end up well. He's not into that Beatle trip, none of us are." And while she was aware that there were still jibes against her, she was feeling far more confident than she had on the tour of the Continent the previous year. "I can remember crying my eyes out in a dressing-room in Europe because I was so scared. Now I know you can get up there and have a good time."

Basically, it didn't matter a jot what the press thought of Linda or Wings. The only real critics were those who paid their hard-earned money at the box office. And the true measure of their opinion was the reaction of the most knowledgeable, hardest-headed and least easily impressed audiences in Britain - those in London. And Londoners took to Wings so well during their two storming, bopping shows at the Hammersmith Odeon that a third concert had to be hastily scheduled due to overwhelming demand for tickets,

The tour officially ended in late May but some cities had been missed and weren't at all pleased. So the group arranged four further dates in Sheffield, Stoke, Leicester and Newcastle (and another at Birmingham that had had to be postponed from May). The first real test of Wings as a performing group had been passed with flying colors. They'd at last established themselves in both major areas of rock activity - they could make hit records and they could fill halls.

Meanwhile, Paul was in demand as a songwriter. Roger Moore kept a diary of his experiences while shooting his first film as James Bond. It was later published - Roger Moore As James Bond (Pan) - and an entry for early 1973 read: "Paul McCartney has written the song and I had lunch today with the man who is arranging the music, George Martin, who was responsible for so many of the Beatles' hits. It is a tremendous piece of music and I will stick my neck out and say that three weeks from its release it will be number 1 in the charts. It's not last year's music, it's not even this year's music, it's next year's."

In the event, that wasn't a bad prediction from an actor in his forties and, presumably, rather out of touch with rock. Live And Let Die reached number 2 in the US charts and 9 in Britain. (The sound-track album by the George Martin

Orchestra which featured the song managed, rather surprisingly, to get to number 21 on the US album charts. A good indication of Wings's selling potential.) It was an untypical Wings record in that it was the lushest, most orchestrated and dramatic production they'd done. Its sound was specifically designed to reflect the dramatic, exciting Bond image. Another example of Paul's versatility and willingness to range outside both the rock format and the critics' preconceived notions of the sort of music he should be making.

With the success of this single (it was nominated for a 1973 Oscar) and the other records that year, as well as the triumph of the British tour, everything looked set fair for the future of the group. But just as they were ready to soar, Wings came crashing to the ground. The percipient might have seen storm warnings raised back in April, 1973 when Henry McCullough told Melody Maker: "I don't suppose we'll be together for ever, I'm sure Paul's got more of a tie to the Beatles than to Wings." Or when Denny Seiwell offered Record Mirror his opinion about a Beatles reunion: "Now that the obstruction in the form of Alien Klein has gone, I should think there's a strong possibility that they will all get together again."

However, both men added that they were committed to Wings. "The band has really progressed as a team," Henry observed. "Everybody wants to make it as a band, whereas before it was just Paul. Wings has all the makings of a great group, but our battle is to keep it as a band and not let it fall apart as it could so easily do. It's worth going at it. I'm there 100 per cent, I know we've got a lot to offer."

Despite these words, by May there was speculation about McCullough's position within the group. The same edition of Disc that carried the review of the Oxford concert also ran a news story under the headline: McCullough To Quit Wings? It read: "Henry McCullough... is poised to quit. Whispers at the weekend... suggest that Henry is unhappy and contemplating a return to Joe Cocker, with whom he played as a member of the famous Grease Band." The story went on to quote an unidentified "close friend" who said: "I know Henry was beginning to feel that he could do a lot more musically than he is with Wings. And one person he appreciates more than any is Joe, who is trying to get a new band together."

As the tour progressed, and Wings were seen to be alight performing outfit, the rumors were somewhat allayed, but shortly before the group was due to record its third album, both Henry and Denny Seiwell quit.

The reasons they left are probably many and varied. They are certainly to do with personalities. A group is a complex organism, it depends upon compromises, on people subjugating a part of their personality for the general good. Any group is going to demand that differences are settled quickly and cleanly. In addition there are always clashes of ego (especially among performers) and disagreements about musical styles. Because Paul had been with the Beatles for so long, he had forgotten how fraught the bringing-together of disparate personalities could be. He admitted as much in an interview: "One thing I tend to forget is the people have to more or less live together and if there's a bit of bitchiness on a tour or during something boring like rehearsals... We need people who make that side of it very easy for each other..."

Henry McCullough had always been something of a loner. His previous record showed that he'd had difficulty slotting himself into a group for any length of time. As Paul said some months after the break: "Henry preferred to lead a more bluesey way of life and he left over musical differences. He was very good at the other stuff but more into blues."

McCullough left shortly before Wings were due to fly to Lagos, Nigeria for recording. He and Paul came to a showdown over styles of playing and he was unhappy about taking directions from Paul. His loss, though sad, was not critical; both Paul and Denny Laine could double on guitar, Denny Seiwell's exit was more dramatic. He phoned to tell the McCartneys he was off only an hour before they were due to fly out. The reason he gave, and Paul passed on to the press, was he didn't want to go to Africa.

It was evidently just the tip of the iceberg and later both Paul and Linda realized that there were deeper motives. A British newspaper quoted McCullough as saying he left because of Linda. "Trying to get things together with a learner in the group didn't work as far as I was concerned," he reportedly groused. Some years later Paul recalled that Henry and Denny would ask why Linda was in the group at all. "I would say: 'I don't quite know. I can't put it into words, but I know there's a good reason for her being here.' "

He said that he was sensitive to their discontents. They felt she was holding the band back. "I could feel this," Linda said. "They thought I was getting the best bits without being any good." It's not difficult to sympathize with McCullough and Seiwell, at least to an extent. It must have been galling for them, as professionals with years of experience, to be slowed down by the faltering attempts of the boss's wife. They were not always alone in that for Paul has revealed: "Perhaps I did have doubts now and again about Linda on keyboard. I did once say to her in a row that I could have had Billy Preston."

After the event the McCartneys could be philosophical about the crack-up of the first band. Linda commented, retrospectively, "That period was almost a relief for Paul. He finally had people with him who cared, those who showed up at the airport. We didn't even know if Denny (Laine) was coming! "And at the time Paul put a brave face on it by telling the press that he wasn't replacing McCullough or Seiwell immediately. The Nigerian sessions were still on. "We are a flexible band and anyway when we are recording I can play the lot myself." For the moment, however, there was no escaping the fact that Wings were broken.

Назад к оглавлению

|